Roy Milton Scott, known by his loved ones as Scotty, and his father took off in a two-seater Piper Cub airplane while overlooking the Bighorn Mountains in Sheridan County, Wyoming, in 1949. This flight was a test for his father to showcase specific maneuvers necessary to receive his commercial pilot license and was the next step in his father’s career; he had already obtained his private license through the GI Bill.

Scotty was in the front seat, so this gave him a panoramic view. His father told him, “Watch this,” and flew the plane into lenticular clouds. The Piper Cub is known for being lightweight and having a cruise speed of about 75 miles per hour. His father pushed the throttle completely back, and the plane’s speed escalated rapidly, which generated an air wave. An air wave occurs when the air around the plane becomes compressed, and shock waves form on the plane’s wings and drag increases drastically. Scotty describes this experience as being lifted by the hand of God. His father flew the plane up to 12,000 feet and had to turn back because there wasn’t enough oxygen left in the cockpit.

On their way back to the airport, his father noticed that the wind was picking up, causing dust from the wheat fields below them to circulate. Since Scotty was in the front seat, he was able to look out the windows around him and see that the wheat was practically lying flat on the ground due to the wind. Once they entered the vicinity of the airport, the marshallers on the runway were signaling him to not go near the airport and to land on the taxiway. As the marshallers were signaling Scotty’s father to land, another plane was approaching the taxiway.

When the marshallers grabbed the straps from the other pilot’s plane to guide him into the hangar, a gust of wind blew his plane backward. The marshallers lost grip of the straps, and the pilot broke his back from the impact. While this was going on, Scotty and his father were still in the air and running low on fuel. When it was Scotty’s father’s turn to land, he flew the plane to hover about 50 feet above the ground. Unfortunately, another gust of wind came through. Once the gust passed them, their plane dropped and crashed onto the taxiway. The marshallers then hauled the plane into the hangar, where Scotty and his father were able to safely exit the plane. Scotty was 12 years old when his father crash-landed the Piper Cub. His admiration for planes and what they can do was awakened following the incident – he knew that wherever he ended up in life, it would revolve around airplanes.

Sixteen-year-old Scotty graduated from Sheridan High School and began his college career at the University of Colorado. He studied aeronautical engineering there, although he never actually worked in aeronautics. When he was a senior in college, he watched Russia launch Sputnik 1 into space, and that inspired him to pursue a career in aerospace engineering.

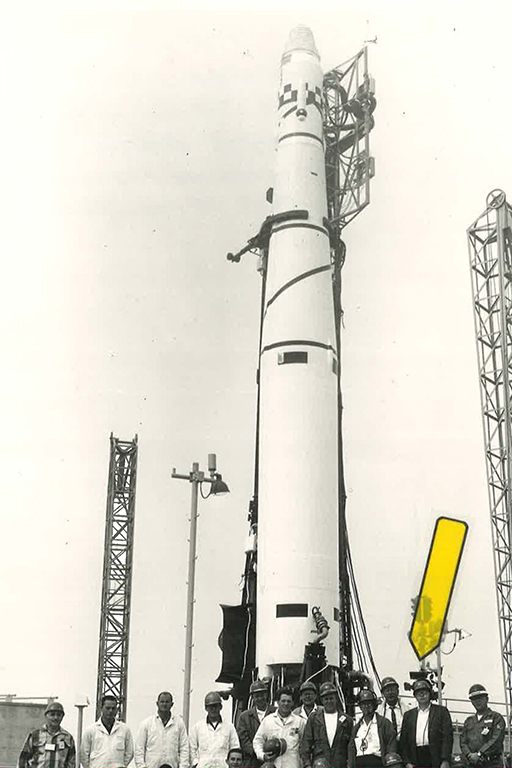

Upon graduating, Scotty was hired at The Douglas Company, an American aerospace corporation in Southern California. Once he began working at Douglas as an aerospace engineer, the company was under an agreement with the U.S. Air Force to begin designing and building launch pads for the Titan missile system. Scotty was subcontracted by the Air Force at Vandenberg Air Force Base in Lompoc, California, to work directly on the Titan program. With tensions running high in the Cold War, President John F. Kennedy was one of the major driving forces behind the Titan program, and he reassured U.S. citizens that the military was prepared for every “what if” scenario.

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty,” said JFK during his inaugural address in 1961.

The Air Force was determined to secure the right people for the Titan program so that it was successful, and Scotty was the right man for the operation. The five launch pads he developed deployed satellites in England against Russia under the mutual assured destruction, or M.A.D., doctrine. This military strategy was created to deter two or more rivals by deploying a nuclear weapon, which would result in complete annihilation of the defender and attacker. Scotty had an extreme weight on his shoulders to guarantee that in the event of a nuclear attack, his engineering would protect the U.S. and its allies.

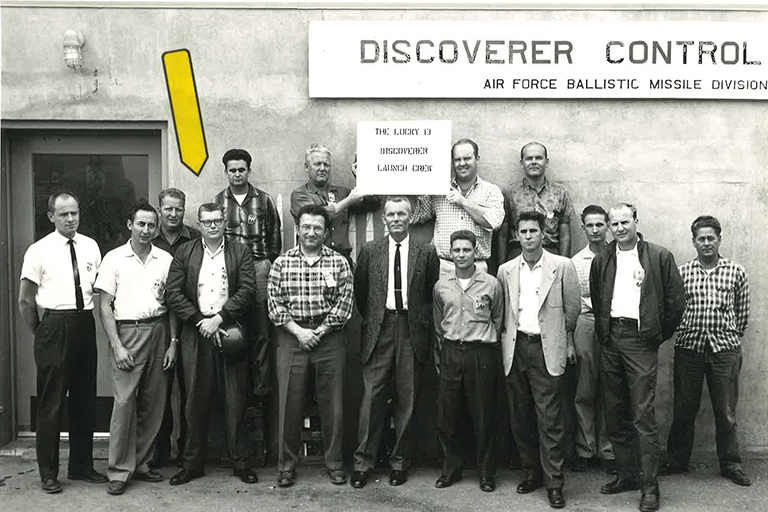

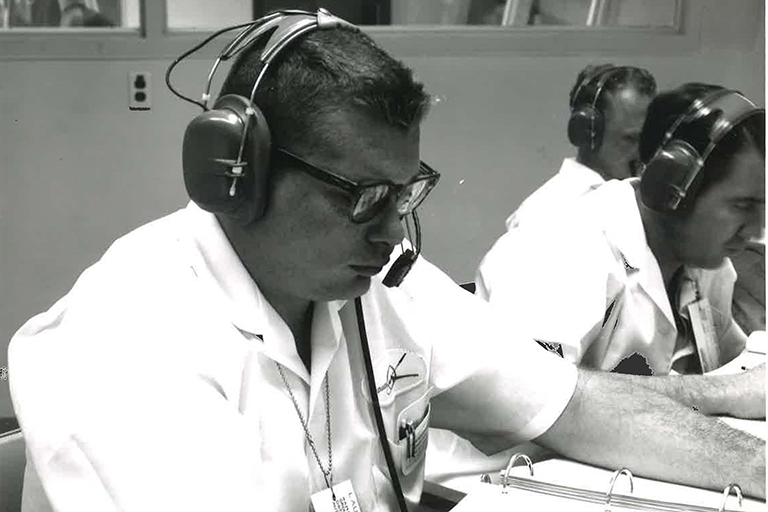

Scotty was also the countdown launch conductor while at Vandenburg. He was responsible for the control parts used to launch research and development satellites into space to test the instrumentation that was used to watch Russia in case they launched nuclear weapons at the U.S.

However, the Air Force didn’t tell Scotty and his peers that they were working with the CIA. The CIA was placing cameras on the satellites to take pictures of and spy on the Soviet Union. Although the Red Scare was presumed to be over during this time, the U.S. continued to distrust the Soviet Union and was fearful of their potential schemes. Scotty explained that when the CIA arrived on base, they were dressed in Air Force uniforms, but he and his peers could tell the difference between civilian and military personnel – they inferred that the government was somehow involved in the program.

Additionally, Scotty worked as a subcontracted system engineer for Skylab, the first U.S. space station launched by NASA, during his time at Douglas. He worked on the third stage of the moon rocket with his team. The rocket was already 20 feet in diameter when they began working on it, and they modified it so that the astronauts could properly orbit the moon. Scotty left his position at Douglas prior to Skylab successfully launching the rocket, but before he did, he wrote a technical specification that included the preliminary design information for NASA and the Air Force to complete what he started.

In between his various assignments at Douglas, Scotty met Lenora, his beloved wife, who also worked at Douglas as the project engineer’s secretary. In January 1964, Lenora’s boss felt compelled to introduce her and Scotty.

Scotty and the project engineer worked closely together on the satellite launches, so the two of them regularly met to discuss plans. One evening, Scotty met with the project engineer, and he brought Lenora with him so that she could take Scotty to the airport for a separate arrangement with the company in Hawaii.

Lenora wasn’t ready to date Scotty when he returned from Hawaii that April. Although he asked her out multiple times, she kindly declined. He asked her out once more, and she couldn’t think of an excuse to give him, so she agreed to go on a date with him. From that moment on, Scotty and Lenora were inseparable. Scotty and Lenora had children from previous marriages, so when they married, they blended their families into one.

From 1969 until his retirement, Scotty worked at Ball Aerospace Company. Ball built the first solar satellites sent to space to take measurements of the sun. He shared that his career began by working on the first space boosters for the Air Force to then working on the first space station for NASA.

In 1990, Scotty had two heart attacks, one in February and one in November, that caused him to retire earlier than he hoped. However, he made the best of his retirement – working on his dream home in Wyoming, fishing, hunting and going on ATV trail rides.

Sheridan is the home of Westview Health Care Center, where Scotty recently received rehabilitation. He returned home to Lenora but has sadly passed away since then.

Throughout his 83 years of life and more than three decades as an aerospace engineer, Scotty took part in several monumental and groundbreaking moments in U.S. history. Even though Scotty was a short-term patient at Westview, he impacted the lives he encountered at the facility through his storytelling and warmth. We share Scotty’s story and brilliance in remembrance of his legacy, and we are grateful to Lenora for giving us this honor.

Life Care operates or manages more than 200 skilled nursing, rehabilitation, Alzheimer's and senior living campuses in 27 states.

Find a Location